Oracle bones provide a glimpse into history

A large quantity of oracle bones excavated from the Yinxu site in Anyang, Central China's Henan province, are housed at a museum there. [Photo provided to China Daily]

On Nov 8, during a total lunar eclipse, a blood moon illuminated the sky. If people missed it, they would have to wait about three years to see the next one.

In the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC), a lunar eclipse was also observed, and the scene was engraved on oracle bones. Including this event, six solar and lunar eclipses, on oracle bones found in existence, have been deciphered by researchers. One solar eclipse was believed to have occurred on Oct 31, 1161 BC.

How people back then reacted to the celestial events is relatively unknown, although it is believed that Shang people began to learn more about observing eclipses. The recordings are helping researchers date the oracle bones and understand the course of the Shang Dynasty, and they can be used as references for further study of the sun-Earth-moon system.

Awe-inspiring astronomical phenomena like an eclipse are among many events and omens noted on oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty. Such inscriptions and the related prayers reveal to people today the many aspects of life back then — led by rules, how members of the aristocracy and commoners lived, including sacrifices, feasts, military acts and harvest, as well as predictions of the sex of an unborn child, safe routes for hunting and the proper day to sell one's ox.

The use of oracle bones as an important method to understand society declined following the rising popularity of referring to I Ching (Book of Changes) in the Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-256 BC).

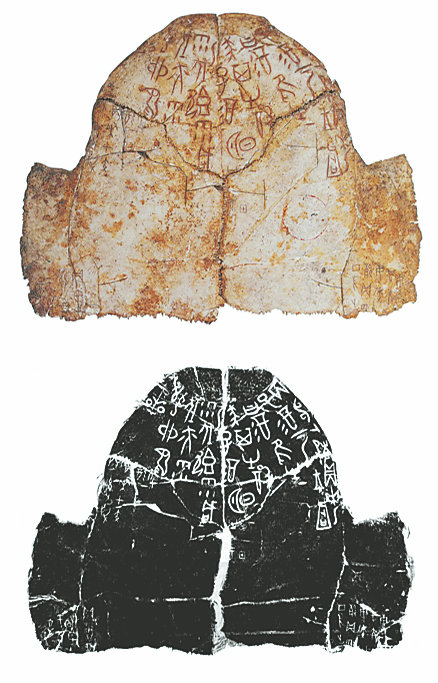

The inscriptions, however, predominantly carved on tortoise shells, cattle scapula and other animal bones, progressed, and are today viewed as the earliest known form of Chinese characters, providing clues to the establishment and evolution of grammar. This writing system anticipated the formation of zhuanshu, or the seal script, and has been integrated into the development of Chinese calligraphy.

A Shang Dynasty oracle bone housed in the National Museum of China in Beijing. [Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

Growing collections

Oracle bones were believed to be first unearthed in Xiaotun village, Anyang, today's Henan province, in the dwindling stages of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The region was once called Yin, serving as the capital of the Shang Dynasty in its late stage.

Villagers had little idea of what they had found and sold the bones to drugstores as traditional Chinese medicine; some people even ground the surfaces flat — having the inscriptions erased — so that they would be accepted by the TCM stores.

The medicines known at the time as "dragon bones" gained the notice of scholars and historians in the late 19th century and they began to study and collect the bones with inscriptions. The discovery was followed by a series of archaeological excavations, primarily in Anyang where the Yinxu site is located. Yinxu, in Chinese, means the ruins of Yin. Over the past 120 years, major systematic excavations have been carried out, boosting the studies of the history of the Shang Dynasty and written Chinese.

A relic site museum has been built at the Yinxu site, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the Chinese oracle bone inscriptions were listed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register program in 2017.

Wang Wei, a member of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says discovering and pinpointing the Yinxu site was the starting point and foundation of exploring the cultures of Xia (c.21st century-16th century BC) and Shang dynasties, and tracing the origins of the Chinese civilization.

Oracle bone found at the Yinxu site. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Feng Shi, a researcher of the Institute of Archaeology affiliated to the CASS, says so far about 150,000 oracle bones have been found and more than 4,000 characters have been recognized, reflecting the many dimensions of the political and social lives of the Shang Dynasty.

He says the discovery of oracle bones and inscriptions has "enriched the content of the Yin culture and people's understanding of the Shang civilization" and is of significance to the study of Chinese writing as "a mature, full-fledged system".

Song Zhenhao, one of the most prominent scholars in the study of oracle bones and a researcher at the CASS, says the script emphasizes the respect for ancestors and family cohesion and other core Chinese values that have been passed on for generations until today.

After the Yinxu site was identified as one where oracle bones were unearthed in 1908, the objects and other artifacts found at the site, such as bronze and jade pieces, also became the target of international buyers, and were transported overseas in large quantities.

Tang Jigen, a leading archaeologist specializing in Shang history and a chair professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, has throughout the years read through artifact catalogs and visited museums abroad. He says, roughly calculated, there are about 50,000 artifacts from the Yinxu site outside the country, and oracle bones account for the majority of such items. The oracle bones have been found in some 14 countries besides China, Song says.

Artists' pursuits

The oracle bone script appeals to not only scholars but also those outside the circles of archaeology and museology.

Among people who brought the oracle bone script to the notice of the international community was Zao Wou-ki (1920-2013), a Chinese-French artist of world acclaim who grew up in a well-to-do family and was surrounded by objects of antiquity, including oracle bones collected by his father, a successful banker.

When Zao arrived in Paris in the late 1940s, where he would live for decades, he explored a distinctive approach to painting. He thought about his family collections and integrated the pictorial forms of the script into his oil works, establishing a semi-abstract style. He developed a body of work later known as the "oracle bone series" that also helped take the script to the world stage.

In an interview with the French magazine Preuves, in 1962, Zao said: "Although the influence of Paris is undeniable in all my training as an artist, I also wish to say that I have gradually rediscovered China," referring to his experimental blending of the elements of the oracle bone script and Chinese ink art tradition with Western oil art.

Chen Nan, a professor at Tsinghua University's Academy of Arts and Design, has invigorated the life of these archaic symbols by featuring them in the biaoqingbao (emoticons) he developed and the artworks he made. And he has launched a font library based on his long-term studies of oracle bone characters.

"Why do we need to know about the writings from thousands of years ago? It is because they embody the clues to our cultural lineage," Chen says.

"I feel it is our obligation to communicate about the charm of the primitive inscriptions with the younger generations and foreigners. And to achieve that goal, we should have an open mind to make the script young, fun and fashionable."

A cup featuring oracle bone script. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Digital technology has also played a greater part in the revival of the oracle bone script. Big data platform Yinqi Wenyuan was put to use in 2019, the year that marked the 120th anniversary of the discovery of the inscriptions, and Song was behind its establishment. The platform gives people huge access to reference and research on oracle bones.

Weeks ago, the National Museum of Chinese Writing, in Anyang, unveiled its first mascot named after Cang Jie, the legendary figure credited with inventing the Chinese writing system.

He is featured on various creative products and put in different digitalized scenarios to tell the tales of Chinese characters.

Recently, the museum opened to the public new exhibition halls under its second-phase construction and a Chinese Writing Park, marking its effort to provide systematic information on the formation and progress of Chinese writing.