Heritage Grid | United States of China”? Wait, the term may be applicable in West Zhou Dynasty !

Over 2,000 years ago, China also had a fengjian system similar to that of Europe, which established numerous states. According to incomplete historical records, from the early Western Zhou Dynasty until 221 BC, when the Qin Dynasty unified the six states and achieved centralization, there were successively more than 140 enfeoffed states in Chinese history. A key difference from the European system was that these states, at least nominally and institutionally, were required to acknowledge the Zhou Son of Heaven (周天子)as the supreme ruler.

During the centuries of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, these states were gradually absorbed or annihilated through intense wars of annexation. By the late Warring States period, the political landscape had coalesced into a pattern represented by seven dominant powers: Qi (齐), Chu(楚), Yan(燕), Zhao(赵), Han(韩), Wei(魏), and Qin(秦)—collectively known as the "Seven Great Powers of the Warring States."

What needs to be underlined is that the Zhou kings granted land to their supporters, making it a system known as fengjian(封建), which has been compared to feudalism(封建) because of the same pronunciation in Chinese, but it was a hierarchical structure, not a federal one.

Scattered across present-day China, these used-to-be capitals of these lands tell distinct stories of regional power, ambition, and cultural splendor. However, only a several are unearthed or can be analysed archeologically. Here are some of these:

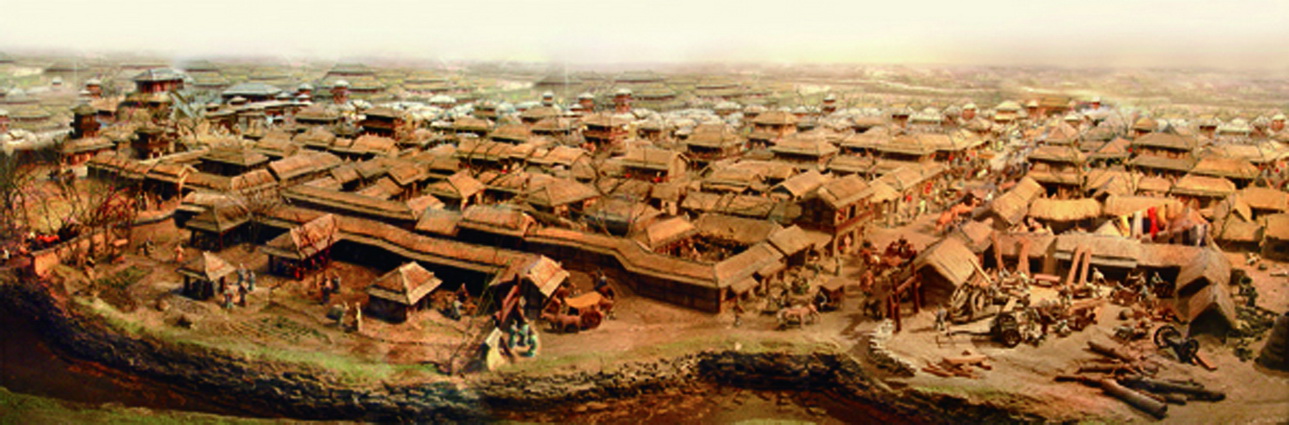

▲The miniature of the ancient Linzi city model

Linzi(临淄), Capital of the Qi State: Situated in modern Shandong province, Linzi was an ancient metropolis. Its ruins feature a distinctive two-city layout: a large outer wall enclosing a public and residential area, with a smaller, fortified inner city nestled in the southwest corner, housing the palace complex. It served as the Qi capital for over six centuries, evolving from a Zhou-appointed garrison into a wealthy and independent power renowned for its intellectual vibrancy and economic might.

Yanxiadu(燕下都), the Secondary Capital of Yan: In Hebei province, the sprawling ruins of Yanxiadu reveal the might of the northern Yan state. It was the largest capital city of the Warring States period, a vast rectangular fortress divided into eastern and western sections by a long interior wall. Its strategic location and massive scale underscore Yan's role as a bulwark against northern tribes and a major contender in the wars of unification.

Handan(邯郸), Capital of the Zhao State: The Handan site in Hebei showcases a classic "品"-shaped palace city known as the Zhaowangcheng. This complex of three interconnected walled sections sat adjacent to a larger, separate "Great Northern City" for commerce and residences. This clear separation of royal and civic spaces highlights the sophisticated urban planning of the late Zhou period.

Qufu(曲阜), Heart of the Lu State: As the fiefdom of the Duke of Zhou's descendants, Qufu in Shandong was a bastion of Zhou ritual culture and tradition. Its roughly rectangular walls, with a central palace area, housed a state that prided itself on preserving ceremonial orthodoxy. Archaeological finds here provide a direct link to the ritual practices and social hierarchies emphasized in classical texts.

Shouchun(寿春城), Final Capital of Chu: Located in Anhui, Shouchun represents the final chapter of the powerful Chu state. Built over an earlier settlement, it served as the last refuge for the Chu court as it retreated before Qin's advance. The layout, adapted to local waterways, and the luxurious artifacts found within its tombs, reflect the distinct southern culture of Chu, which blended Zhou customs with its own vibrant traditions.

These capitals invite a natural and productive comparison with medieval European feudalism. Personal loyalty oaths, decentralized military, and landholding characterized both systems. However, the contrasts are equally instructive. For instance, the inheritance of titles and lands in the Zhou world was almost exclusively patrilineal, unlike in many European realms, where female succession could occur. Moreover, the ultimate ideological goal under the Zhou system was the maintenance of a universal "tianxia" (all-under-heaven) order centered on the Son of Heaven. In contrast, Europe's political ideal was often a balance of powers among the Pope, the Emperor, and the kings.

The Zhou's "fengjian" system was a protracted, large-scale experiment in decentralized territorial governance. Its story—from consolidation to fragmentation and eventual re-unification—is a crucial chapter in global political history.