Heritage Grid | Tongwancheng: Archaeology’s Sole Witness to Xiongnu Urbanism

Rising from the southern edge of the Mu Us Desert like a phantom fortress, the white walls of Tongwancheng—"the city ruling ten thousand"—gleam under the northern Shaanxi sun. Built not of stone or timber, but of qinji earth: a mix of clay, sand, lime, and crushed rice grits steamed into bone-colored slabs. To touch its surface today is to feel the chilling ambition of Helian Bobo, the Xiongnu chieftain who declared himself emperor in 407 CE and demanded a capital to outshine any in China. "I shall unify all under heaven and rule over myriad lands," he proclaimed. Thus, Tongwancheng was born—and with it, the only surviving urban testament to the Xiongnu, the nomadic empire that once shook Eurasia.

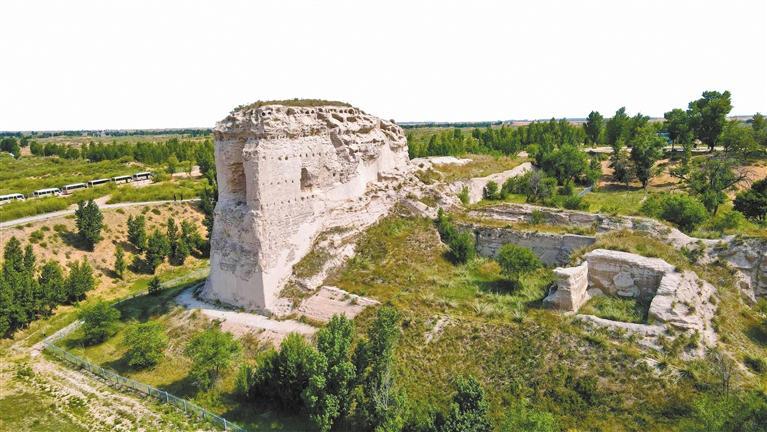

▲ The remains of the Tongwancheng

Building Utopia on the Steppe

In 413 CE, Helian Bobo marshaled 100,000 laborers—many conscripted from conquered Han Chinese, Xianbei, and Qiang communities—for a project both revolutionary and grotesque.

According to the historic recordings, using technology adapted from Chinese wall-building traditions, workers steamed soil into hardened panels. Quality control was enforced with a dagger: if a blade could penetrate a finished slab more than one inch, the builder was executed. If it failed to pierce at all, the tester was killed for negligence. "Bury them in the walls," came the order.

The edict 'Execute the builder if an awl penetrates one inch [into the wall]' was utterly cruel. Driven by whips, blades, and axes, the city was constructed with extraordinary fortification. However, the claim that 'corpses were mixed into the earth as building material' is likely either a historical misrecord or a misinterpretation of sources. Archaeological investigations to date have found no evidence of substantial human remains within the walls. The reason is straightforward: incorporating large amounts of organic matter into rammed earth would weaken structural integrity, not strengthen it. Chigan Ali, the project overseer, was vicious but hardly foolish—he would never have pursued such a counterproductive measure detrimental to everyone involved.

Despite the wild wind in the northwest loess plateau, the core walls still stand 10 meters high today, their material resisting erosion like concrete. Archaeologists note the near-absurd sophistication: angled bastions ("mamian") to deflect siege engines, staggered gateways trapping attackers in kill zones, and corner watchtowers surveying the Hongliu River valley—a deliberate echo of Xiongnu grassland sentinel traditions.

The Twenty-four-year Empire

Tongwancheng’s glory proved as ephemeral as desert rain. By 418 CE, Helian Bobo sat enthroned in its whitewashed palace, having sacked the Jin Dynasty’s capital at Chang’an(Xi'an for today). Yet in 427, Northern Wei armies breached its defenses. By 431, the Xiongnu state vanished—barely outlasting its founder. What followed was stranger still: ethnic fusion. For 500 years, Tang Dynasty officials repurposed the city as a multicultural garrison town (Xiazhou), where Sogdian merchants traded silk beneath Buddhist niches carved into Xiongnu towers.

An Ecological Parable

The Mu Us Desert’s advance holds Tongwancheng’s deepest warning. Ninth-century (around the Tang dynasty) poets described dunes "spinning like storms" until grasses vanished and the Hongliu River silted. Deforestation by soldiers and settlers stripped the land. By the Song Dynasty(11th century), the "green pastures and clear streams" Helian Bobo once admired had become a sea of sand. Today, the ruins lie 120 km south of Inner Mongolia’s drifting sands—a monument not just to empire, but to ecological hubris.

Why Tongwancheng Haunts Us

Tongwancheng’s value transcends archaeology: it counters the stereotypes of "barbarian" transience, and its complex hydraulics and urban grid reveal a sophisticated nomadic urbanism. In the city, the grain silos held six-year reserves; workshops cast iron arrowheads in Chinese-Xiongnu hybrid designs.

Eurasia’s Forgotten Bridge: Before the Mongols, the Xiongnu dominated trade from Rome to Chang’an. A 2021 excavation near the West Gate uncovered Sassanian Persian coins and Byzantine glass—proof of its Silk Road centrality.