Heritage Grid | The Twin Pillars of a Dynasty: The Dual Capital System of Han China (Chang-an)

Imagine a conversation across time between the founding emperors of two mighty Han dynasties. Liu Bang (Emperor Gaozu of the Western Han), having just unified a war-torn China in 202 BC, paces in his provisional court. His advisor, the brilliant strategist Zhang Liang, points to a map. "My Lord," Zhang might have said, "Luoyang lies at the heart of the Central Plains, a crossroads of tradition and commerce. It seems the obvious choice for our capital". Yet, Zhang ultimately argued against it, deeming Luoyang's terrain too vulnerable: "Its territory is small, not exceeding several hundred li, the land is thin, and it is exposed to attack on all four sides; this is not a state for military prowess". His finger then traced westward to Guanzhong, the Land Within the Passes. There, amidst formidable mountains and fertile plains, lay the ruins of a Qin dynasty capital. "Chang'an," Zhang proclaimed, "is a natural fortress, a 'golden city stretching a thousand li' and a 'land of abundance'". Liu Bang was convinced. Thus began one of history's most enduring geopolitical blueprints: the Dual Capital System, where Chang'an was established as the primary political and military capital, and Luoyang was designated the secondary, ritualistic eastern capital.

This was not merely a practical arrangement but a masterstroke of statecraft.

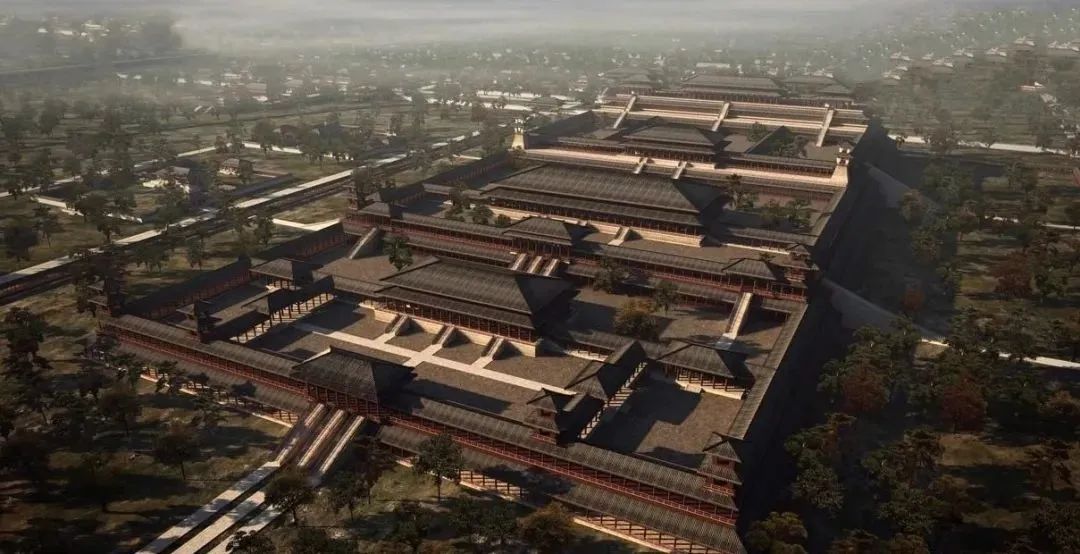

The Western Han, inheriting the Qin empire's framework but wary of its rapid collapse, needed to balance raw power with cultural legitimacy. Chang'an (near modern Xi'an) became the engine of imperial control. Built upon the foundations of earlier palaces, it was designed as an awe-inspiring administrative and military fortress. The city's irregular, roughly square walls, stretching over 25 km in circumference, followed terrain and existing structures, hinting at its pragmatic and expansive growth. Its grandeur was meant to overawe. The Weiyang Palace, the central administrative complex, housed the emperor and his vast bureaucracy. Between it and the Changle Palace for the empress dowager lay the formidable Imperial Armory (Wuku), a stark symbol of the state's military might, with foundations of massive buildings for weapon storage and production.

▲An artistic impression of the Weiyang Palace (Image by the Han Chang'an City Weiyang Palace Museum)

Luoyang, by contrast, was cultivated as the "virtuous" counterpart and a bridge to the eastern elites. While not the primary seat of power, its status as the sacred Eastern Capital was critical. It was the ceremonial heart, associated with the ancient Zhou dynasty's concept of ruling from the "center of the world" (Zhongguo, a term famously appearing on a Western Zhou bronze vessel, the He Zun, excavated near Luoyang, which reads: "The king began to take residence in Chengzhou... dwelling in this Central State"). This ideological weight made Luoyang indispensable for rituals affirming Heaven's Mandate. Furthermore, it served as a vital hinge in both the economy and demographics. To strengthen Chang'an's base and weaken potential eastern rivals, the Han implemented a policy of "strengthening the trunk and weakening the branches," forcibly relocating powerful clans from the eastern plains to the Guanzhong region around Chang'an. Luoyang acted as a key node in managing this vast, restive eastern territory.

The system's brilliance lay in this functional dichotomy, brilliantly captured later in literature. The historian Ban Gu, in his Fu (rhapsody) "The Two Capitals", has a fictional defender of Chang'an boast of its cosmic alignment, mountainous defenses, and dazzling palaces filled with rare treasures from across the realm. This was Chang'an's reality: a cosmopolitan, wealthy, and fiercely protected command center. When the reformist usurper Wang Mang briefly ended the Western Han in 9 AD, he too recognized the system's value, drafting plans to formally elevate Luoyang's status as an eastern capital, a vision that would soon be realized in a dramatic reversal.

▲The archaeological site of the Weiyang Palace

That reversal came with the restoration of the Han under Liu Xiu (Emperor Guangwu). In 25 AD, after the civil war, he faced the same choice as his ancestor Liu Bang. His power base, however, was firmly in the eastern plains. Returning to a Chang'an damaged by war, he made a decisive pivot. He established Luoyang as the primary capital, the Eastern Capital (Dongdu), and demoted Chang'an to the status of Western Capital (Xidu). The Twin Pillars remained, but their weights had completely shifted. The second part of our story explores this dramatic flip and its profound consequences for the empire's soul, urban form, and legacy.

TO BE CONTINUED in part II The Eastern Pivot and Eternal Legacy

Related articles

-

Chang'an: The Timeless Ancient Capital of China

Chang'an: The Timeless Ancient Capital of ChinaMore

-

Yao Dong: Characteristic dwellings of the Loess Plateau

Yao Dong: Characteristic dwellings of the Loess PlateauMore

-

Heritage Grid | Tongwancheng: Archaeology’s Sole Witness to Xiongnu Urbanism

Heritage Grid | Tongwancheng: Archaeology’s Sole Witness to Xiongnu UrbanismMore

-

Qinqiang: The Enduring Legacy of China's Ancient Clapper Opera

Qinqiang: The Enduring Legacy of China's Ancient Clapper OperaMore

-

Heritage Grid | The Sacred Peaks: How these Five Mountains Forged Chinese's Identity

Heritage Grid | The Sacred Peaks: How these Five Mountains Forged Chinese's IdentityMore