Heritage Grid | The Legacy of Chinese Academies: Education, Ethics, and a Dialogue with Athens

In the rich tapestry of global educational history, the Chinese Shuyuan, or academies, stand as a profound testament to China’s enduring pursuit of knowledge and moral cultivation. For over a millennium, these institutions were not merely schools but vibrant centers of intellectual debate, spiritual growth, and cultural preservation. Much like the famed Athenian Academy of Plato in ancient Greece, Chinese academies served as sanctuaries of learning, where the goal was not just scholarly achievement but the cultivation of character and wisdom. This article explores the birth of China’s great academies, the stories of the luminaries they nurtured, their unique educational philosophy, and how they compare with their Western counterpart.

The golden age of Chinese academies dawned during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), an era marked by both cultural flourishing and political uncertainty. In response to the limitations of the official examination system, which emphasized rote memorization of Confucian classics for bureaucratic advancement, private academies emerged as beacons of intellectual freedom. These institutions were often established in secluded, picturesque settings, away from the political intrigues of the capital, symbolizing a retreat for pure scholarship.

The most celebrated among them are the Four Great Academies:

White Deer Grotto Academy (Lushan, Jiangxi)

Yuelu Academy (Changsha, Hunan)

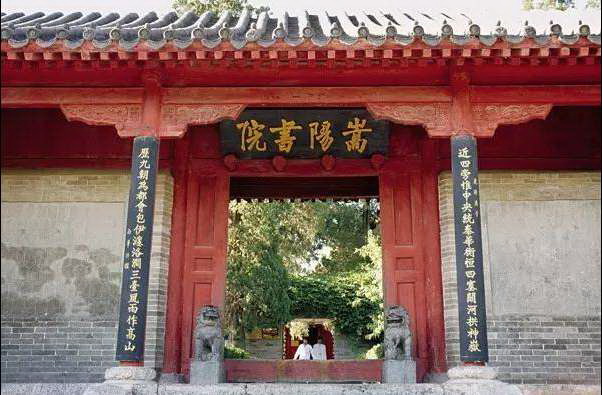

Songyang Academy (Dengfeng, Henan)

Yingtian Academy (Shangqiu, Henan)

Unlike official schools, which were state-run and geared toward producing bureaucrats, academies were typically founded by renowned scholars and supported by local communities. They emphasized personal moral development and critical interpretation of classics, creating a dynamic space where education was a lifelong journey rather than mere preparation for exams.

Each of the Four Great Academies is immortalized by the legends of the thinkers who shaped them.

At the White Deer Grotto Academy, the Neo-Confucian master Zhu Xi (1130–1200) revived and expanded its educational activities. He drafted a set of academy rules that emphasized self-reflection, respectful discourse, and the investigation of things to extend knowledge. His teachings integrated philosophical inquiry with everyday ethics, influencing East Asian thought for centuries.

The Yuelu Academy became famous for the dialogues between Zhang Shi and Zhu Xi. They famously debated the relationship between “human nature” and “the way,” drawing hundreds of scholars to witness their intellectual exchanges. This tradition of “huiyang” (meeting and debating) underscored the academy’s commitment to collaborative truth-seeking.

Fan Zhongyan, the renowned statesman and poet, studied at the Yingtian Academy. His dictum, "Be the first to worry about the world’s troubles and the last to enjoy its pleasures,” encapsulates the Confucian ideal of social responsibility that academies sought to instill.

At Songyang Academy, the philosopher Cheng Hao (1032–1085) lectured on the unity of knowledge and action. He urged students to cultivate an “inner sage” through quiet reflection and earnest practice, blending Buddhist and Daoist insights with Confucian ethics.

The Chinese academy system was built on several core principles that distinguished it from official education:

Self-Directed Learning: Students were encouraged to explore texts independently and form their own understanding under the guidance of a master.

Moral Cultivation: The primary aim was to develop virtuous individuals who would contribute to social harmony, not just skilled officials.

Intimate Teacher-Student Relationships: Learning was personalized, with mentors offering spiritual and intellectual direction.

This holistic approach stood in stark contrast to the rigid, exam-focused “official learning.” While the state system produced competent administrators, the academies nurtured thinkers, artists, and moral leaders.

Interestingly, the Chinese Shuyuan and Plato’s Athenian Academy (c. 387 BCE) shared remarkable similarities despite arising in entirely different cultural contexts. Both were informal institutions centered around a great master (Plato, Zhu Xi). Both emphasized dialogue, debate, and the pursuit of wisdom beyond practical skills. Both sought to cultivate virtuous individuals—whether the Chinese “junzi” (noble person) or the Greek “philosopher-king.”

However, key differences existed. The Athenian Academy prioritized rational inquiry, logic, and abstract philosophy, often questioning traditional beliefs. In contrast, Chinese academies focused on the interpretation of canonical Confucian texts, emphasizing ethical conduct, social harmony, and alignment with cosmic principles. While the Greek model celebrated rhetorical persuasion and public debate, the Chinese ideal valued quiet introspection, scholarly diligence, and reverence for tradition.

Although the traditional academy system faded in the early 20th century, its spirit lives on. The emphasis on character building, the integration of knowledge and ethics, and the model of learning as a communal, lifelong journey continue to resonate in modern educational theories. As we seek to reform contemporary education, which often prioritizes utility over wisdom, the legacy of the Chinese Shuyuan—and its parallel with the Athenian Academy—reminds us that true education must nurture both the mind and the soul.

Related articles

-

Yin Shang Culture: Yinxu, Oracle Bones and Bronze Ware

Yin Shang Culture: Yinxu, Oracle Bones and Bronze WareMore

-

Longmen Grottoes: The Peak of Chinese Stone Carving Art

Longmen Grottoes: The Peak of Chinese Stone Carving ArtMore

-

Heritage Grid | Luoyang Unearthed: Where China’s Golden Age Took Root

Heritage Grid | Luoyang Unearthed: Where China’s Golden Age Took RootMore

-

Heritage Grid | Yinxu, the Birthplace of Oracle Bone Script—the DNA of Modern Chinese Characters

Heritage Grid | Yinxu, the Birthplace of Oracle Bone Script—the DNA of Modern Chinese CharactersMore

-

Yangshao Culture: The Most Influential Prehistoric Civilization in China

Yangshao Culture: The Most Influential Prehistoric Civilization in ChinaMore

-

Heritage Grid | The Sacred Peaks: How these Five Mountains Forged Chinese's Identity

Heritage Grid | The Sacred Peaks: How these Five Mountains Forged Chinese's IdentityMore