Sands of time protect an ancient treasure

Site of Western Xia ceramic production in Northwest China fascinates archaeologists.

This archaeological site, along the Helan Mountains in the Ningxia Hui autonomous region, had been buried under the sand for about a millennium. Once unveiled, it seems as if its shards of history, broken yet glittering, are hoping to tell their story.

The ruins of 13 porcelain kilns were found by archaeologists in Helan county, Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia, at the Suyukou site, which covers about 40,000 square meters, according to a conference of the National Cultural Heritage Administration earlier this month in Beijing.

Though only 1,000 sq m, including two kilns, were excavated at the site from 2021 to 2022, the joint archaeological team from the Ningxia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Shanghai-based Fudan University has been amazed and delighted by key discoveries.

Exquisite white porcelain artifacts for various functions — bowls, plates, cups, vases and kettles — jointly portray a picture of a high quality everyday life.

These findings indicate their exceptional status, linking them with Western Xia, or Xixia (1038-1227), a powerful regime that once ruled Northwest China until it was conquered by Genghis Khan.

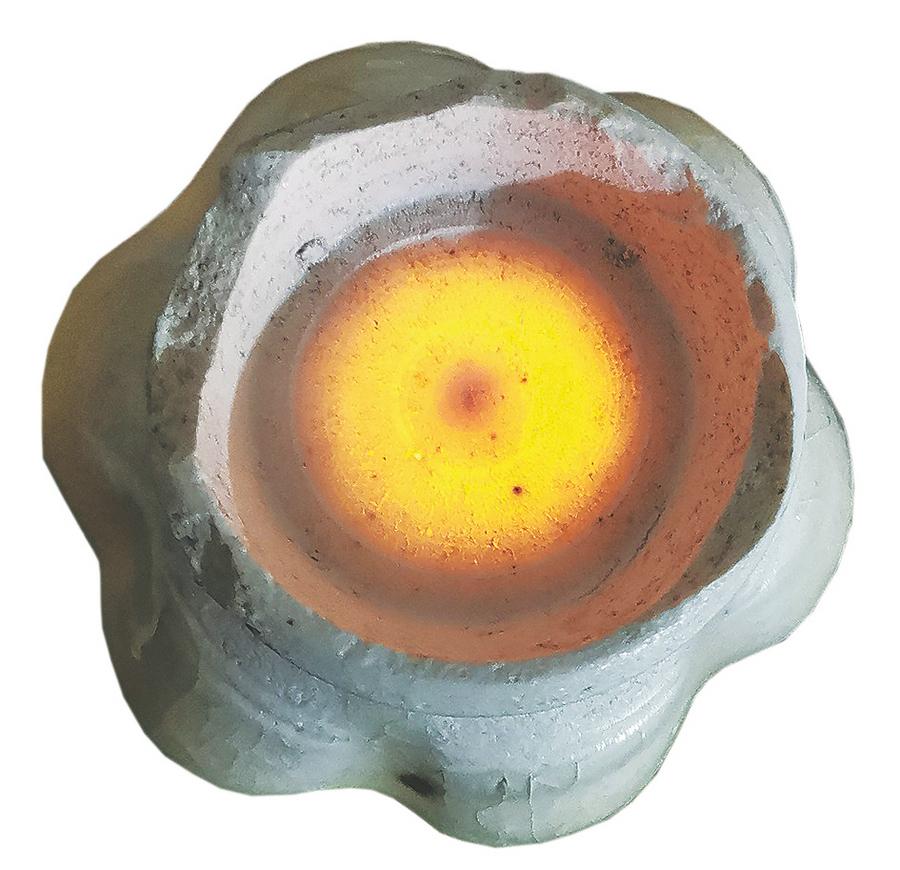

According to Chai Pingping, an archaeologist with the Ningxia institute, who briefed the conference in Beijing, the Chinese character guan ("the official") was found to be marked on many manufactured tools like saggers — the boxes made of fireclay in which delicate ceramics are fired.

Through analysis of materials, the new findings also echoed the significance of those previously unearthed white porcelain pieces from a royal mausoleum and residences of Western Xia rulers since the 1980s. Archaeologists used to be confused as to where exactly those exquisite artifacts were produced. Now, they have an answer.

"Suyukou should be the guanyao (official porcelain kilns serving the royal family) of Western Xia," Chai says. "It is also the oldest-known ruins of Western Xia ceramic production."

The site also fills a gap of archaeological sites related to refined white porcelains in Northwest China.

"A complex porcelain-making industry was thus unveiled," he says.

On Wednesday, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences also listed the Suyukou site as one of "the six most important new archaeological findings in China in 2022". That annual list is widely seen as one of the country's top honors bestowed upon archaeological projects.

"We could not simply presume that previously discovered white porcelain was made in a royal kiln, just because it was exquisite," Wang Guangyao, a researcher at the Palace Museum in Beijing, explains. "We needed archaeological proof and now we have found it."

The Song Dynasty enjoyed a booming economy, and its culture prospered. In Qin's eyes, highly developed ceramics showcase the pinnacle of the era's handicraft industry.

"Before the Song Dynasty, China's porcelain production was generally centered in the east and south of the country, but it expanded to a much larger geographic area since," Qin says. "Western Xia benefited from that trend."

Researchers once believed that the upper classes during the Song era preferred celadon ceramics, due to an impression left by literature of the time, but in recent years, archaeologists have been given cause to think again.

"According to our excavations, they probably loved white porcelain more," Qin says. "We can see Western Xia rulers also favored it based on the studies of Suyukou. Despite conflict, they embraced not only the exquisite ceramics, but also the refined Song culture."

Wang from the Palace Museum also suggested viewing the findings in a context of the bigger picture, during the time of Western Xia and Song, when communication among ethnic groups contributed to the forming of the Chinese nation.

He points out that archaeological findings demonstrate a fact: Song people, Tangut people, or Khitan people who founded the Liao Dynasty (916-1125) in North China, tended to establish the royal kilns near their capital cities.

"Perhaps, this format of management was shared by various ethnic groups at that time," he says.

Qin also explains that most refined Chinese porcelain varieties were produced in southern China because, in the north, the porcelain clay has less silicon. That means it would be more difficult to sinter and form a perfect porcelain shape.

But how did Western Xia artisans in Suyukou make such outstandingly exquisite products?

Their secret formula was to deliberately add quartz to the clay, as shown by the mining sites around Suyukou. The end result was clay of supreme quality, equal to that of Jingdezhen.

"It's quite shocking for us to find such a technical breakthrough by the Tangut people," Qin says.

Zhu Yanshi, deputy director of the Institute of Archaeology with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, considered Suyukou an ideal example of great luck.

"You rarely find such a complete chain of porcelain production that can help solve so many academic puzzles, let alone one that represents the cutting-edge technology of its time," he says. "New light could be shed on studies of Western Xia history as a whole."

Related articles

-

Tri-colored Figurines of Musicians on Camelback

Tri-colored Figurines of Musicians on CamelbackMore

-

China's Tibet discovers earliest cave tomb built 3,000 yrs ago

China's Tibet discovers earliest cave tomb built 3,000 yrs agoMore

-

Dehua porcelain int'l exhibition held at UN

Dehua porcelain int'l exhibition held at UNMore

-

Han Lacquered Ding with Cloud Design

Han Lacquered Ding with Cloud DesignMore

-

Exquisite jade artifacts on display at Shanxi Museum

Exquisite jade artifacts on display at Shanxi MuseumMore

-

Cultural Relic: Boat-shaped Painted Clay Pot

Cultural Relic: Boat-shaped Painted Clay PotMore