Repairing the past, restoring our future

Visitors appreciate rock carvings in Baodingshan, one of the five major clusters in Dazu district, Chongqing. JIANG DONG/CHINA DAILY

Cave temple protection in Chongqing requires effort, talent and pride in rich heritage

A massive array of stunning rock carvings are receiving ever more attention and protection as they regain their past glory.

Stone-paved stairs, steep but not long, lead one up to Beishan (Northern Mountain) that sits about 2 kilometers in the northwest of Dazu district, Chongqing.

A wooden corridor built against the rock wall then reveals itself.

Walking down the shaded path, hundreds of grottoes, as dense as beehives, hit the eye from the side wall.

The corridor has served as a shelter for the Buddha figurines, deities and animals that were delicately carved out of the rock as early as the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

The rudimentary wooden structure was built in the 1950s to shelter the exposed rock carvings, says Jiang Siwei, head of the Academy of Dazu Rock Carvings based in the district.

"It looks simple but is very practical, and keeps the grottoes from the elements," Jiang says, adding that a similar structure would have been in place when the grotto was first built in ancient times.

"Moreover, it blends in with the surroundings."

The Beishan cluster is part of the Dazu Rock Carvings, which were inscribed onto the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1999, the second grotto temple entry from China, after the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province.

Those grotto temples were believed to have been introduced into China from India via the Silk Road in the third century. As the Buddhist art form evolved, it absorbed local artistic elements.

A girl examines the Thousand-Armed Avalokitesvara, the goddess of mercy, in Baodingshan, Dazu district. JIANG DONG/CHINA DAILY

In addition to exquisite Buddha images and scriptures, characteristic of the country's grotto temples elsewhere, Dazu carvings highlight mundane scenes that urge people to be filial, conduct themselves properly and refrain from greed.

The carvings have also enjoyed a unique status for mixing Buddhism with indigenous beliefs like Confucianism and Taoism.

To date, more than 50,000 statues or carved images on the cliffs in the district have been put under protected cultural relic status, among which the most characteristic are the carvings in Beishan, Baoding, Nanshan, Shimen and Shizuan mountains.

Beishan boasts the largest rock carvings.

Wei Junjing, governor of Changzhou, was the initiator of the first carvings at the site in the late Tang Dynasty. More carvings were added under the auspices of officials, the gentry, scholars and monks. The cluster on its present scale was completed during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), consolidating the reputation of the statues for exquisite and elegant craftsmanship.

Archaeologists have proved that they showcased the development in the nation's folk Buddhist beliefs and stone carving art styles during the 9th to the 13th centuries.

Over the past decades, workers have tried to restore them to their original beauty.

Since mountains in the area have large quantities of sandstone, cracks have appeared due to geological movement, while the damp and hot southern climate results in underground water with natural chemicals, endangering the stone carvings and their carrier — the rock.

"You can see some crack lines and calcium precipitations have formed over parts of the cave walls," Jiang says.

Rock carvings at a cave temple in Beishan cluster in Dazu district, Chongqing. JIANG DONG/CHINA DAILY

Various approaches were tried to prevent the groundwater from encroaching on the carvings, such as digging diversionary tracts, but these efforts were in vain due to the complex water distribution in the mountains.

"It worked on the mountain water on the surface but failed to keep off the water flowing from the distant mountain area," Jiang explains.

It was not until 1992, when they ingeniously came up with the idea of digging holes and tunnels right below the caves to divert water from the temple areas, that the water erosion problems have been effectively addressed.

Since then, they've kept close tabs on any new cracks appearing, the biggest threat to those rock carvings.

"They affect the stability of the rock body," Jiang explains.

The initial observations used rough but ready methods, such as measuring the lengths of those cracks.

In 2015, they started to work on caves where the cracks were classified as hazardous.

"We have to make predictions over the development of any cracks on the cave, like what is the borderline point that would comprise steadiness and under what conditions the cave might collapse," Jiang says.

"It requires calculations, and equipment monitoring and practical experience before coming up with intervention measures and removing the hazards," he says.

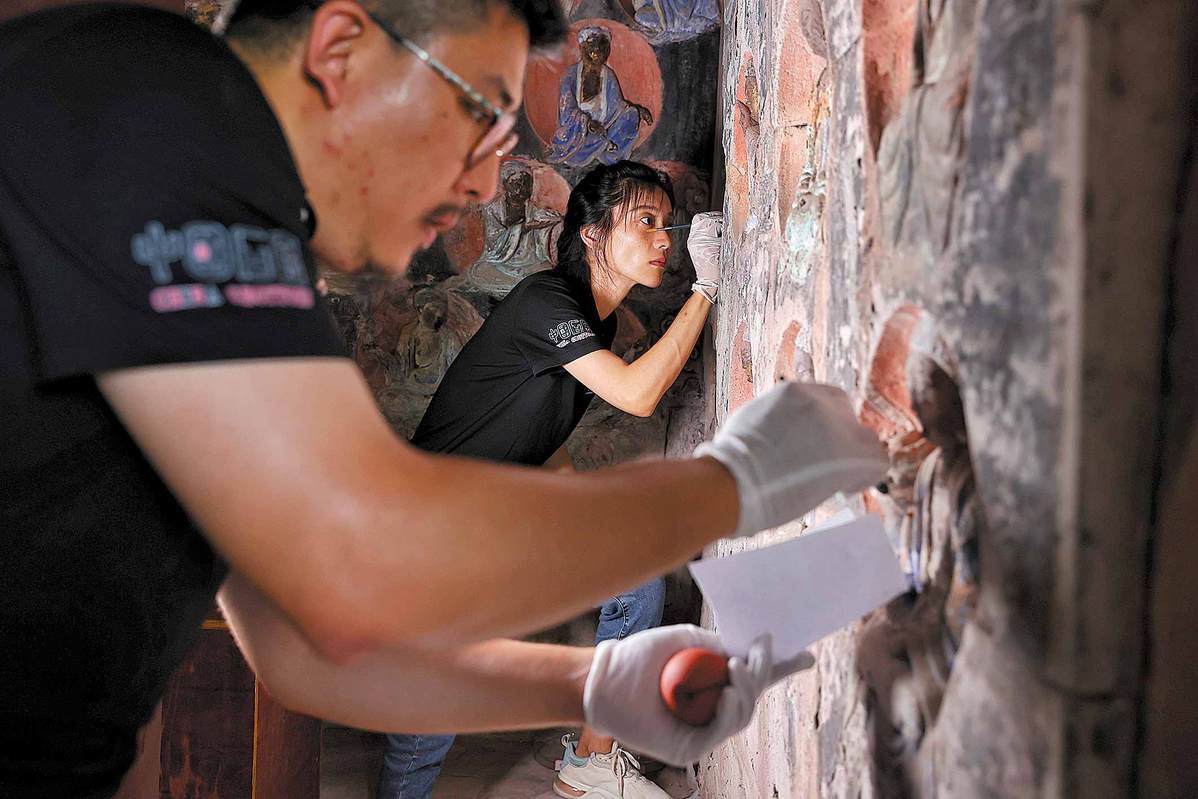

Local restorers work on rock carvings at Xiaofowan site in Dazu. JIANG DONG/CHINA DAILY

Cave No 168 is one example and it took three years to finish reinforcement procedures.

The Institute of Geology and Geophysics, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, was invited to survey the land first before operations were carried out.

"The theoretical calculation alone is not enough, since many problems can arise during practice," Jiang says.

For example, exactly how much grouting pressure should be applied to fill the cracks in the rocks needs constant experimentation.

"If it's too small, it can't reach certain fine cracks, but if it's too big, new cracks will open," Jiang says, adding that the time for the grout to solidify between the rocks also needs to be observed and modified.

Cave No 168 has had a concrete beam and bolt system placed to secure its thin roof, while an advanced electronic monitoring system has been installed to keep track of changes, such as crack growth, wall pressure and air, over the following five years in the cave.

All the data are transported to an electronic monitoring center at the Academy of Dazu Rock Carvings.

The center was established in 2012 and has been equipped with the advanced monitoring system since 2019. It has received data on 70 indicators of artifacts and surrounding environment from all major stone carvings protection sites across Dazu.

Rock carvings at a cave temple in Beishan cluster in Dazu district, Chongqing. JIANG DONG/CHINA DAILY

"Some data have to be acquired by our inspectors," says Feng Xuemei, an officer who has been working with the center for five years.

All of the previous data have been collected and moved to the new system, which has now amassed more than 7 million data entries.

"One of our responsibilities is to compare new data with the past to ensure everything is all right," Feng says.

Caps have been set on tourist numbers and the environment, ranging from humidity, temperature to air quality.

"When any anomaly comes up, we will assign personnel to the site and conduct an intervention," Feng says.

One of the most prominent restoration projects involves an eight-year restoration of the Thousand-Armed Avalokitesvara, the goddess of mercy (known as Guanyin in Mandarin), in Baodingshan, one of the five major rock carvings sites in Dazu.

The statue, a stone carving with gold plating and color elements, had suffered damage, ranging from broken fingers and peeled-off gold foil, after it stood the test of time for more than 800 years.

"Observed at close quarters, it looked pocked with scars," recalls Chen Huili, director of the academy's conservation center, who led the restoration project.

She and her team did a good deal of research and experiment before settling on the repair materials and methods.

Workers carry heavy segments at the Shuchengyan site in the district's Zhongao town. JIANG DONG/CHINA DAILY

"They have to best fit the Guanyin statue, which is of sandstone texture, as well as take into account high temperature and humid environment," Chen explains, adding that every decision and move were made based on studies of the statue and related history and scientific papers.

For example, she and her team used to go to Sichuan, Hebei and Shandong provinces to study rock carvings, trying to draw inferences for mending the statue's broken right hand.

"It was repaired by the ancients, but was inconsistent to the original," Chen says.

She then proposed to create a detachable hand based on the symmetric features of the statue, because there is still one minor inconsistency in the angle of the remaining bracelet buckle.

"Therefore, future fixes can be easier to be applied, when more is discovered," Chen says.

Now, the restored statue looks solemn and shines, and has become a major attraction.

The Academy of Dazu Rock Carvings has also worked with international organizations to repair local rock carvings.

At Shuchengyan site in the district's Zhongao town, a cave temple has recently finished preliminary restoration, thanks to joint efforts between a cultural heritage cluster from Italy and the Academy of Dazu Rock Carvings.

The project started in 2018, and a series of experiments and analysis were then conducted by both sides on gold foil, paint, rock and microorganisms, as well as repairing techniques, for a year before restoration eventually kicked in.

"The temple was very popular in the old times and visited a lot by locals," says Ruan Fanghong, an official with the project.

As a result, many rock carvings were damaged.

The two sides applied synthetic enzymes to remove impurities from the paint, and used polyvinyl alcohol to paste the gold foils back.

"Now, several years have passed, and the restored parts have maintained very well," Ruan says.

In the last decade, 246 million yuan ($33.1 million) has been put into 24 restoration projects in Dazu, according to local authorities.

In addition to the major rock carving sites, a comprehensive conservation and research project has been launched since 2020 to cover more than 60 medium- and small-sized sites.

According to the Dazu academy's plan, about 700,000 yuan will be allocated for the renovation of each site. By 2025, all potential hazards to these medium- and small-sized sites will be addressed.

After years of hard work they are on the homestretch of completion, Chen says.

"We'll lay more of a focus on restoring them to the original beauty in the future, while keeping them under close watch for their safety."

Related articles

-

Monks unfurl giant artworks as Shoton begins

Monks unfurl giant artworks as Shoton beginsMore

-

Was the place where Chinese monk Jianzhen set off on his sixth voyage to propagate Buddhism in Japan

Was the place where Chinese monk Jianzhen set off on his sixth voyage to propagate Buddhism in JapanMore

-

Noted monk spreads Buddhist tradition

Noted monk spreads Buddhist traditionMore

-

Rare cliff carving Buddhist statues found in Tibet

Rare cliff carving Buddhist statues found in TibetMore

-

Giant thangka on display at Tibetan monastery

Giant thangka on display at Tibetan monasteryMore

-

New architecture in Canada promotes Buddhism

New architecture in Canada promotes BuddhismMore