Heritage Grid | Gaoling: Unsealing the Tomb of Cao Cao and the Truth Behind the Legends

The year is 2008. In a village in Anyang, Henan, archaeologists begin a rescue excavation of a severely looted Eastern Han dynasty tomb. What they would uncover over the following year would not only solve a mystery over 1,700 years old but also ignite one of the most heated public debates in modern Chinese archaeology: had they truly found the final resting place of Cao Cao, the famed and formidable strategist of the Three Kingdoms? Today, the Anyang Gaoling (曹操高陵), or Cao Cao Mausoleum, stands not as a silent relic but as a vibrant museum and a cultural touchstone.

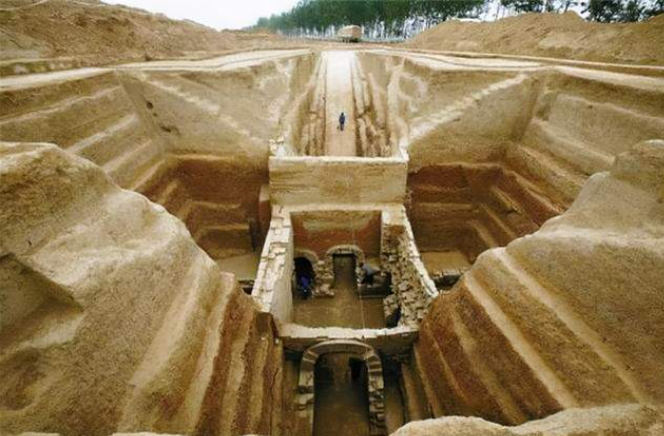

▲ The legacy of CaoCao's tomb

Its story is a gripping tapestry woven from hard archaeological evidence, enduring literary myths, and a concerted effort to separate the historical man from the legendary villain.

The Man and the Myth: Why Anyang?

To understand the significance of the tomb's location, one must understand Cao Cao's unique position in history. He was the de facto ruler of northern China in the late Eastern Han, a brilliant military leader, a poignant poet, and a political figure who wielded power "above the emperor" without ever taking the throne for himself. In 216 AD, he was formally enfeoffed as the King of Wei by Emperor Xian, with his royal domain centred on the city of Ye (near modern-day Linzhang, Hebei), which borders Anyang.

As explained by Pan Weibin, lead archaeologist of the Cao Cao Gaoling project, feudal lords of the era were expected to be buried within their own territories. True to this custom and his own previously issued decree (The Final Order), Cao Cao, who died in Luoyang in 220 AD, was brought back to be interred in Xigaoxue, west of Ye. The choice of Anyang was not random but a powerful statement of his lifelong authority over the Kingdom of Wei.

Solving the "Seventy-Two False Tombs" Mystery

No discussion of Cao Cao's tomb is complete without addressing the most famous legend: that of the Seventy-Two False Tombs (七十二疑冢). Popularised by the Ming dynasty novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, the tale claims the cunning Cao Cao ordered the construction of dozens of decoy tombs to prevent his real grave from being found and desecrated.

Archaeologists and historians have conclusively debunked this as a later literary fabrication. These mounds, once thought to be decoys of Cao Cao, are actually Northern Dynasty noble tombs. The discovery of a single, clearly identifiable Gaoling in Anyang definitively puts this romanticised myth to rest.

The Evidence and The Controversy

The announcement in December 2009 that the tomb was Cao Cao's Gaoling was met with immediate public fascination and intense scholarly scrutiny. The debate was fierce, with questions raised about the evidence.

The archaeological team built a robust evidentiary chain. Key artifacts included:

Stone Tablets with Inscriptions: Several Guī-shaped stone plaques bore the critical text "魏武王常所用..." (Personally used by King Wu of Wei...), directly linking items to Cao Cao's posthumous title.

Imperial-Level Ritual Objects: The tomb contained items like twelve ceramic ding (鼎) tripods and a jade guī of specific dimensions, which were explicitly reserved for emperor-level rites according to historical records like 《后汉书·礼仪志》.

The Remains: The skeletal remains of a male, approximately 60 years old, aligned with the historical record of Cao Cao's age at death.

Evidence of Joint Burial: Traces of a secondary burial matched historical accounts that Cao Cao's wife, Empress Bian, was buried with him a decade after his death.

Despite this, controversies swirled for years, ranging from claims that the evidence was forged to suggestions that the tomb belonged to other historical figures. Scholars have noted that this public debate, while challenging, ultimately highlighted the importance of public archaeology and spurred more rigorous research. Today, the consensus within the academic community is solid: the Anyang Gaoling is authentic.

A Legacy in Stone and Soil: The Tomb's Features and Value

The tomb itself is a "甲"-shaped structure, oriented east-west, with a sloping passage leading to main and rear chambers flanked by four side chambers. Its design and contents speak volumes.

True to Cao Cao's well-documented advocacy for frugal burial (薄葬), the tomb is striking for what it lacks compared to other royal tombs of the era. There is no trove of lavish gold or jade. Instead, most offerings are small, crudely-made ceramic miniatures (明器)—models of buildings, wells, and even a pigsty—symbolic rather than valuable. This practice reflected his personal ethos and the turbulent, resource-scarce times in which he lived.

Its value as cultural heritage is immense. It is the first and only scientifically excavated imperial mausoleum from the Han-Wei transition period (c. 220 AD). It provides an irreplaceable benchmark for understanding the burial customs, rituals, and material culture at a pivotal moment in Chinese history.

From Excavation to Education: The Gaoling Today

The story doesn't end with the archaeology. In 2023, the Cao Cao Gaoling Site Museum opened to the public. It masterfully integrates the protected tomb site with expansive exhibition halls, displaying over 900 restored artifacts. Exhibits like "History Across a Millennium" use artifacts, historical documents, and multimedia to contextualise Cao Cao's life, his era, and the archaeological journey, which attracts loads of visitors.

However, a fascinating and heartwarming trend has emerged among young Chinese visitors to the Cao Cao Gaoling (Cao Cao Mausoleum) in Anyang, especially during the Qingming Festival. Alongside traditional offerings, many now symbolically place a few Ibuprofen capsules at the tomb of the legendary Three Kingdoms ruler. This act, far from being disrespectful, is a humorous and empathetic form of tribute rooted in internet culture—offering the historically famous "headache-suffering king" some "time-travelling pain relief."

▲ The offering table for Cao Cao, adorned with Ibuprofen.

This phenomenon directly stems from Cao Cao's enduring literary image. In the classic novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, his debilitating headaches are a recurring motif, often flaring up at moments of immense stress, strategic dilemma, or emotional shock. His legendary refusal of the physician Hua Tuo's proposed craniotomy, driven by fear and pain, cemented this association in popular memory. For modern youth, the Ibuprofen capsule becomes a symbol of cross-millennial empathy. It represents a personal, compassionate connection, breaking down the formal distance of history and saying, "We understand your pain," in a contemporary language.

Nowadays, the Anyang Gaoling is far more than a tomb. It is a bridge across centuries, connecting us to the real Cao Cao—the ruler, general, and poet—behind the theatrical white-faced villain. Its discovery resolved ancient mysteries, weathered modern controversies, and ultimately enriched our global understanding of China's past. It stands as a powerful testament to how archaeology can illuminate history, transform legend, and offer the world a key to unlocking one of its most fascinating civilisations.

Related articles

-

Heritage Grid | The Legacy of Chinese Academies: Education, Ethics, and a Dialogue with Athens

Heritage Grid | The Legacy of Chinese Academies: Education, Ethics, and a Dialogue with AthensMore

-

Heritage Grid | The Silent Cities of Mangshan: China’s Valley of Kings

Heritage Grid | The Silent Cities of Mangshan: China’s Valley of KingsMore

-

Heritage Grid | Luoyang Unearthed: Where China’s Golden Age Took Root

Heritage Grid | Luoyang Unearthed: Where China’s Golden Age Took RootMore

-

Longmen Grottoes: The Peak of Chinese Stone Carving Art

Longmen Grottoes: The Peak of Chinese Stone Carving ArtMore

-

Yin Shang Culture: Yinxu, Oracle Bones and Bronze Ware

Yin Shang Culture: Yinxu, Oracle Bones and Bronze WareMore

-

Yangshao Culture: The Most Influential Prehistoric Civilization in China

Yangshao Culture: The Most Influential Prehistoric Civilization in ChinaMore