"Investigating Things to Extend Knowledge": A Spark of Scientific Spirit in Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism?

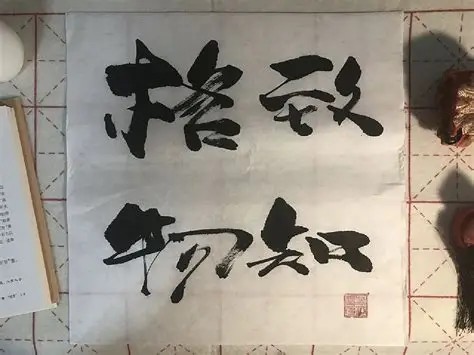

Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism (10th–17th centuries) introduced the concept of gewu zhizhi (格物致知), often translated as "investigating things to extend knowledge." At first glance, it may sound abstract, but it mirrors early scientific curiosity. Think of it like a medieval European scholar dissecting plants to understand nature’s patterns—Chinese thinkers like Zhu Xi (1130–1200) urged students to observe the natural world systematically. For example, studying a tree’s growth wasn’t just about botany; it was a way to grasp universal principles (li), akin to how Newton’s apple led to gravity theories.

However, gewu zhizhi wasn’t pure science. While figures like Zhu Xi emphasized empirical observation, their goal was moral wisdom, not technological progress. Imagine a chemist today researching molecules not for medicine but to understand life’s harmony. Still, this tradition encouraged questioning and evidence—traits foundational to modern science. Later, during the Ming Dynasty, Wang Yangming (1472–1529) critiqued over-reliance on external data, arguing true understanding comes from inner reflection. This debate—between objective inquiry and intuition—echoes today’s discussions in education and AI ethics.

Though not a scientific revolution, gewu zhizhi reflects an ancient Chinese attempt to bridge observation and wisdom. For global audiences, it’s a reminder that science-like thinking has multiple cultural roots, not just European ones. Like Arabic scholars preserving Greek texts or Indian mathematicians inventing zero, China’s Neo-Confucians added their own puzzle pieces to humanity’s quest for knowledge.